During its January term, the Illinois Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Cowper v. Nyberg, a case from the Fifth District posing a novel question: does a prisoner have an implied right of action against the circuit clerk and county sheriff for failing to accurately calculate the credit he or she is due against a prison sentence for presentence incarceration? Our detailed report on the facts and lower court opinions in Cowper is here.

During its January term, the Illinois Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Cowper v. Nyberg, a case from the Fifth District posing a novel question: does a prisoner have an implied right of action against the circuit clerk and county sheriff for failing to accurately calculate the credit he or she is due against a prison sentence for presentence incarceration? Our detailed report on the facts and lower court opinions in Cowper is here.

The plaintiff in Cowper pled guilty to three felony counts in 2011 and was sentenced to 27 months. The sentencing order included a lengthy recitation of the days the plaintiff had already spent in custody, for which he was to receive credit against his sentence. A month later, the plaintiff filed a motion to recalculate the credit, but the State didn’t respond for five months – by which time the plaintiff had already been released. When the State ultimately answered the motion, it conceded that it had underestimated the credit the plaintiff was entitled to by 191 days.

The plaintiff sued the Circuit Court Clerk and the County Sheriff, alleging that they had a tort duty under Section 5-4-1(e)(4) of the Corrections Code, 730 ILCS 5/5-4-1(e)(4), to correctly calculate the length of the credit. The trial court dismissed the action for failure to state a claim on defendants’ motion, but the Fifth District reversed.

Counsel for the Circuit Court Clerk led off the argument by conceding that the number of days’ credit provided by the sheriff to the Clerk and forwarded to Corrections had been incorrect. Nevertheless, the Clerk had merely done what he was required to do under the statute. The plaintiff’s remedy was what he had done in the trial court – to file a motion seeking to have his credit recalculated. There are no allegations in the complaint that the Clerk had done anything more than what the statute required – to pass along the calculation provided by the Sheriff. But the Appellate Court’s opinion would require that the Clerk – indeed, all 102 Circuit Court Clerks in the state – make independent investigations of information not readily available to them in order to double-check calculations from sheriffs. Counsel argued that the Supreme Court had found implied private rights of action only when the statute would be practically ineffective without one. But the purpose of the Sentencing Code, counsel argued, is to protect the public. Justice Theis noted that counsel hadn’t argued in his brief that a motion for recalculation was plaintiff’s proper remedy; the Clerk had argued that the remedy was the grievance procedure under 730 ILCS 5/3-8-8 of the Code. Counsel responded that he was adding to his argument. Plaintiff had both the remedy of filing a grievance, and the additional remedy of a motion to recalculate. Justice Theis pointed out that the plaintiff had only had the opportunity to respond to the grievance argument, and had argued that the grievance procedure related only to misconduct during incarceration. Counsel conceded that the plaintiff had no longer been in prison when he filed his complaint, but he had been when he discovered the miscalculation. Justice Theis asked what happened with the plaintiff’s motion to recalculate. Counsel answered that the plaintiff’s attorney had not brought the matter to the attention of the court. Counsel concluded by arguing that if one applies the Court’s jurisprudence on implied rights of action, the correct conclusion is that none exists here. The statute certainly doesn’t authorize a claim, and the consequence of implying one would be for the courts to be flooded with claims arising from all kinds of errors. After all, counsel argued, implied rights of action couldn’t be found under only one section of the Code.

Counsel for the plaintiff followed. He agreed that the plaintiff had filed a motion to recalculate almost immediately after discovering the error, and no answer had been filed for five months. Justice Thomas asked whether that proved the defendant’s point that a motion is the plaintiff’s remedy. Counsel answered that plaintiff had received no benefit from winning the motion. Justice Thomas suggested that even though the timing didn’t work out in this case, that didn’t make the remedy inadequate. Counsel answered that requiring a motion to recalculate means that the prisoner will have to wait in prison for a motion to be heard before the error can be corrected. Counsel noted that the Clerk argued that he had merely transmitted the numbers provided by the Sheriff, but he said that the case is just at the pleading stage. The credits which were received from the Sheriff and the number transmitted to Corrections were all questions of fact which could be resolved later. The Chief Justice asked whether the Clerk would be exonerated if he merely transmitted the numbers received from the Sheriff, and counsel said yes, the Clerk has no independent duty to verify. Counsel denied that his claim would lead to a flood of sentencing-related litigation. Justice Thomas noted that the Court has said that an important consideration in determining whether a right of action is implied by a statute is whether a statute is intended to be remedial. Was the relevant section of the Code remedial? Counsel said no, but all four factors prescribed by the Court for determining whether to imply a right of action were satisfied. Justice Thomas noted that the Court’s cases say that where a statute provides no consequence for failure to comply, it is directory, not mandatory. Given that the Code doesn’t include a consequence for failing to transmit the proper credits, does that mean the Code is directory? Counsel said yes. Justice Thomas asked whether it was a curious result to imply a private right of action for violating a directory statute. Counsel said no, since there is no other remedy which will cause compliance. Every factor found in the cases weighs in favor of an implied right of action, counsel argued. Plaintiff was clearly a member of the class which the Code was intended to affect. An implied right of action was clearly consistent with the underlying purpose of the statute – to prevent arbitrary and oppressive treatment of prisoners and to restore offenders to useful citizenship. Chief Justice Garman asked whether it made any difference whether the miscalculation was intentional or negligent. Counsel said here, it did not – admittedly, the Clerk hadn’t done anything intentional. Counsel continued with the factors from the cases. Certainly, this injury was one which the statute was intended to prevent. The Code provisions were intended to prevent adjudicated offenders from being kept beyond their lawful sentences. The final factor is whether an implied right of action is necessary for an adequate remedy. Counsel argued that a motion was not an adequate remedy, and the grievance procedure didn’t apply, since the injury hadn’t happened during the plaintiff’s prison term. The Department of Corrections is duty bound to enforce the sentencing order, counsel acknowledged; there would be nothing that the Department could have done, even if it had agreed with the plaintiff’s position. The Chief Justice asked whether there would be a cause of action regardless of the length of time which a prisoner was detained past his or her sentence, and counsel said yes. All four factors for determining whether there’s an implied right of action weighed in favor of the Fifth District’s decision, counsel concluded, and without one, plaintiff would have no recourse for the error.

Counsel for the Clerk rose in rebuttal, arguing that it was the duty of plaintiff’s lawyer to pursue his motion to recalculate. Justice Theis asked whether there was any indication in the record what happened to the motion, and counsel said no. The plaintiff hadn’t brought the motion to the trial court’s attention, but nevertheless, that was his remedy.

We expect Cowper to be decided in three to four months.

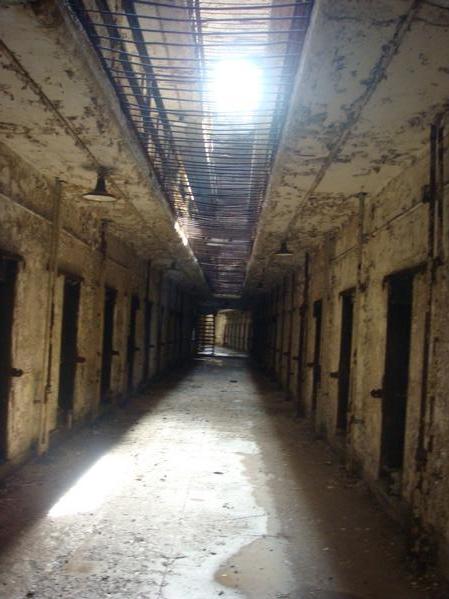

Image courtesy of Flickr by ForensicBones (no changes).