[The following post was originally published on Law360.com on February 12, 2015.]

[The following post was originally published on Law360.com on February 12, 2015.]

For the last two years (see here and here), we’ve taken a close statistical look at the previous year’s decisions from the Illinois Supreme Court to see what insights could be gained about the court’s voting patterns and decision-making dynamics. In 2014, the court once again achieved unanimous decisions in quite a high fraction of its civil cases. When the court was occasionally divided, it was the three Republican justices who most often formed the majority, joined by one or more of their Democratic colleagues.

For 2014, the court decided 27 civil cases, plus an additional 34 criminal and quasi-criminal, attorney discipline and mental health commitment cases. As has been the case in recent years, more than 80 percent of the civil docket arose from final judgments and orders. The court decided five cases each where the primary issue was civil procedure or government and administrative law. The court decided four cases each in tort and constitutional law, three in property law, two each relating to domestic relations and public pensions, and one each in election law and employment law.

The percentage of the court’s docket involving dissents at the appellate court dropped this past year from its recent trend; only 14.8 percent of the civil cases involved dissents below. In contrast, 23.5 percent of the court’s criminal, disciplinary and mental health commitment cases involved dissents at the appellate court level. Curiously, the percentage of the civil docket arising from unpublished Rule 23 orders at the appellate court increased significantly in the past year — up to 40.7 percent of the civil docket. The remaining docket was similar, with 32.4 percent of the criminal, disciplinary and mental health commitment cases arising from unpublished orders.

The court’s civil unanimity rate returned to something much closer to its recent trend line this past year, up from 58.8 percent in 2013 to 77.8 percent in 2014. The court’s unanimity rate in its criminal, disciplinary and mental health commitment dockets was similarly high, with 79.4 percent of all cases being decided unanimously.

Once again, the court produced decisions much more quickly in 2014 when there was no dissent. Unanimous civil decisions came down an average of 100.71 days after oral argument — down slightly from the 2013 mean lag time of 103.7 days. Cases involving dissents averaged 193.83 days after oral argument. Unanimous decisions from the court’s criminal, disciplinary and mental health commitment caseload tended to come down significantly quicker, averaging 78.19 days under submission in 2014. Nonunanimous decisions in those areas averaged 186.14 days under submission.

The court reversed in whole or in part in 77.8 percent of its civil cases in 2014. This result is significantly above the court’s trend in recent years. With the exception of 2009 and 2012, the court’s reversal rate in civil cases has fluctuated around the 50 percent mark in civil cases every year since 2000. The court’s reversal rate was significantly lower in criminal, disciplinary and mental health commitment cases in 2014: only 42.4 percent.

Once again, Chicago’s First District comprised a significant portion of the court’s civil docket — 48.1 percent. Eight of the 13 civil cases the court decided from the First District — 61.5 percent — were reversed. Reversal rates were down in civil cases from the Third and Fourth Districts, but remained relatively steady for the Second District. The Fourth District — home of the state capital of Springfield — has performed well in recent years on the court’s civil docket, with a three-year floating reversal rate of only 44.4 percent. Meanwhile, the court reversed all three civil decisions it heard from the Fifth District. Since 2012, the court has reversed 90.9 percent of the civil cases it has heard from the Fifth District.

The court’s 2014 record in criminal, disciplinary and mental health commitment cases was somewhat different. Only 28.1 percent of the docket arose from the First District, and the reversal rate for First District cases collectively was only 44.4 percent. The Second and Fourth District fared quite well this year before the court in such cases, with only 20 percent and 16.7 percent of those two courts’ decisions being reversed. The Third Circuit did nearly as well, with 40 percent of its criminal, disciplinary and mental health commitment decisions being reversed. On the other hand, 80 percent of the Fifth District’s decisions falling on this side of the docket were reversed.

Justice Anne B. Burke wrote for the court’s majority most often this past year in civil cases, with six majority opinions. Justices Robert R. Thomas and Mary Jane Theis wrote five each, Justices Charles E. Freeman, Thomas L. Kilbride and Lloyd A. Karmeier three each, and Chief Justice Garman one. Turning to the criminal, disciplinary and mental health commitment side of the docket, Chief Justice Rita B. Garman led the court with seven majority opinions. Justices Freeman, Kilbride and Thomas wrote six each, Justices Karmeier and Theis four each, and Justice Burke one.

There were comparatively few written dissents in civil cases this year. Justice Freeman led the court with three dissents in civil cases, with Justices Burke, Kilbride, Theis and Chief Justice Garman writing one each. Dissents were no more common on the other half of the docket, with Justice Burke writing four, and Justices Karmeier, Theis and Chief Justice Garman writing one each.

One way of understanding the dynamics of a court is by looking at which justices are most often in the majority when the court is divided. For 2014, Justices Thomas and Karmeier voted with the majority in every one of the court’s nonunanimous civil decisions. The chief justice was right behind, voting with the majority 83.3 percent of the time. Justice Theis voted with the majority in two thirds of divided cases, and Justices Burke, Freeman and Kilbride joined the majority in half of such cases. The pattern is confirmed by confining the sample to the most closely divided civil cases — cases with two or three dissenters. Chief Justice Garman and Justice Theis voted with the majority in three-quarters of such cases, Justice Burke in half, and Justices Freeman and Kilbride in only one-quarter.

There was evidence of a cohesive center on the other side of the docket as well. The chief justice and Justices Thomas, Karmeier and Kilbride voted with the majority in 85.7 percent of nonunanimous criminal, disciplinary and mental health commitment cases. Justice Theis was next, voting with the majority 71.4 percent of the time, with Justice Freeman (57.1 percent) and Justice Burke (42.9 percent) behind. Five members of the court — the chief justice and Justices Thomas, Karmeier, Theis and Kilbride — voted with the majority in eighty percent of the court’s two- and three-dissenter cases on the criminal and quasi-criminal side of the docket.

We turn next to agreement rates between pairs of justices. Justices Thomas and Karmeier voted together in nearly all nonunanimous cases (100 percent civil, 71.4 percent criminal). The chief justice voted with Justice Thomas (83.3 percent/85.7 percent) and Justice Karmeier (83.3 percent/57.1 percent) most of the time as well.

As for which members of the court were most likely to vote with the three Republican justices in closely contested cases, that depended on which side of the docket one reviewed. On the civil side, Justice Theis voted with Justices Thomas and Karmeier two-thirds of the time in such cases, and with the chief justice half the time. Justices Kilbride and Freeman were not far behind Justice Theis. Both voted with the chief justice in two-thirds of nonunanimous civil cases, and with Justices Thomas and Karmeier in half. In contrast, the Democratic members voted together significantly less often. Although Justices Burke and Freeman, and Freeman and Kilbride each voted together in two-thirds of nonunanimous civil cases, Justices Burke and Kilbride agreed in only one third of such cases. Justices Burke and Theis, and Freeman and Theis, voted together in only 16.7 percent of nonunanimous civil cases.

Turning to the criminal, disciplinary and mental health commitment side of the docket, Justice Kilbride was the most likely to vote with the centrist members in closely contested cases, voting with Justice Karmeier in every case, with Justice Thomas 71.4 percent of the time, and with the chief justice 57.1 percent of the time. Justice Theis voted with Justice Karmeier in such cases nearly as often — 85.7 percent of the time — but with Justice Thomas (57.1 percent) and Chief Justice Garman (42.9 percent) less often. Justices Freeman and Burke were the least likely members to vote with the centrist bloc in such cases. Justice Freeman voted with the chief justice in such cases only 57.1 percent of the time, and with Justices Thomas and Karmeier in 42.9 percent of cases. Justice Burke voted with the chief justice 42.9 percent of the time, and with Justices Thomas and Karmeier only 28.6 percent of the time.

The court asked 760 questions during arguments of civil cases decided during 2014: 335 to appellants during their opening remarks, 328 to appellees and 97 during rebuttal. Justice Thomas asked 238 questions. Justice Burke was second with 147, and Justice Theis right behind with 145. After Justice Theis came Chief Justice Garman with 86 questions, Justice Karmeier with 73, Justice Kilbride with 49 and Justice Freeman with 37. Appellants were asked an average of 17 questions per argument, appellees 13.1. The most active arguments were WISAM 1 Inc. v. Illinois Liquor Control Commission (45 questions for the appellant), and People ex rel. Madigan v. Burge (30 questions to the appellee).

Although every appellate lawyer wants questions from the bench, once again the data suggested that all things being equal, a barrage of questions may not be a good sign. Winning appellants averaged 12.95 questions per argument, losing appellants 26.63. Winning appellees averaged 9.71 questions, losing appellees 14.94. Appellees received more questions than their opponents 11 times in 2014’s civil cases, and they lost all 11. On the other hand, appellants prevailed in five of the 13 civil cases where they received the most questions. In nonunanimous reversals, prevailing appellants received an average of 16.83 questions to 17.17 for the appellees. In unanimous reversals, appellants averages 11.15 questions to 13.73 for the appellees.

Six of the seven justices averaged more questions to appellants than to appellees. For four justices — Chief Justice Garman (1.9/1.4) and Justices Burke (3.5/2.5), Freeman (1.1/0.2) and Theis (3.5/2.0), the difference is comparatively significant; for Justices Kilbride (1.0/0.9) and Thomas, (4.7/4.4), the difference is smaller. Justice Karmeier averaged 1.4 questions to each side.

Dividing the cases into unanimous and divided opinions reveals interesting distinctions. Justices Freeman (2.7/0.7) and Karmeier (2.5/1.0) tended to ask more questions to appellants when the court was divided, while Chief Justice Garman (2.2/1.2) and Justice Thomas (7.7/3.4) asked appellees somewhat more questions on nonunanimous courts. On the other hand, Justices Thomas (5.1/3.3) and Theis (4.2/1.0) averaged more questions to appellants when the Court was unanimous.

Once again, close attention to the Justices’ questions gave hints as to how they were likely to vote. Chief Justice Garman (2.2/1.7) and Justices Burke (6.1/1.9) and Theis (6.3/1.8) averaged more questions to appellants that they ultimately voted against than appellants they voted for. Justices Burke (2.7/2.0), Thomas (6.1/1.4) and Theis (2.4/1.5) each averaged more questions to appellees they ultimately voted against. To look at the data another way, Chief Justice Garman (2.2/1.6) and Justices Burke (6.1/2.0), Freeman (0.7/0.1) and Theis (6.3/1.5) each asked more questions of appellants than appellees when they voted to affirm. Justices Burke (2.7/1.9), Thomas (6.1/3.1) and Theis (2.4/1.8) tended to ask more questions of appellees than appellants when they voted to reverse.

Our review of the data for the Illinois Supreme Court’s 2014 civil decisions suggests three lessons for counsel: (1) the court continues to achieve unanimity in a very high fraction of its cases; (2) when the court is unable to agree, the three Republican justices generally are in the majority; and (3) counsel can make educated inferences about what is likely to happen by paying close attention to the questions at oral argument.

For more of our ongoing statistical analysis of the Illinois Supreme Court’s civil decisions since 2000, join us at the Appellate Strategist‘s sister blog, the Illinois Supreme Court Review.

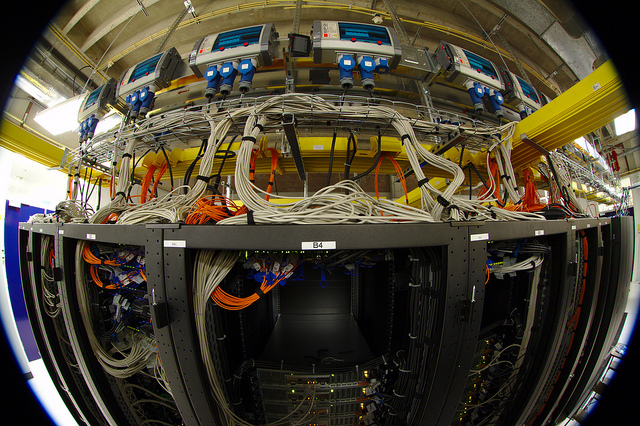

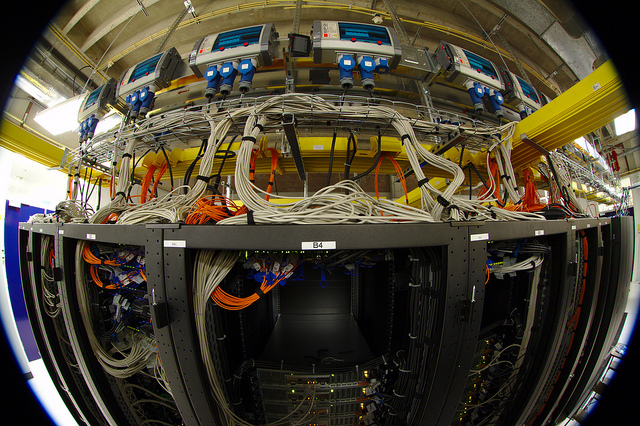

Image courtesy of Flickr by Dennis Van Zuijlekom (no changes).

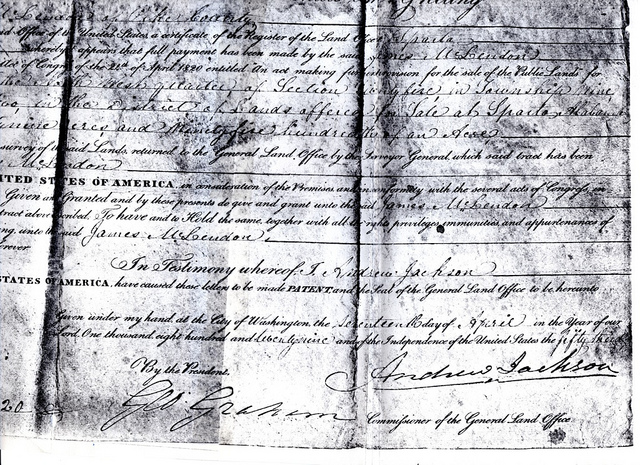

Section 2-1401 of the Illinois Code of Civil Procedure provides that courts may grant relief from a judgment on petition made within thirty days of the original entry of the judgment. The statute further provides that the old common law writs which served similar purposes, such as writs of error coram nobis and coram vobis, bills of review and similar techniques are all abolished.

Section 2-1401 of the Illinois Code of Civil Procedure provides that courts may grant relief from a judgment on petition made within thirty days of the original entry of the judgment. The statute further provides that the old common law writs which served similar purposes, such as writs of error coram nobis and coram vobis, bills of review and similar techniques are all abolished.