In the closing days of its September term, the Illinois Supreme Court agreed to decide a question relating to the operation of Section 2-1401 of the Code of Civil Procedure: under what circumstances is the apparent lack of diligence of the party itself sufficient to justify denying the motion? In Warren County Soil & Water Conservation District v. Walters, the Third District denied a motion to set aside on the grounds that the defendant had not demonstrated adequate diligence.

The plaintiff Soil and Water Conservation District filed suit against the defendants, charging that defendants had wrongfully removed approximately 54 trees, worth just over $17,000, from plaintiff’s property. The plaintiff purported to state claims of trespass, conversation, quantum meruit, negligence, and one for violation of the Wrongful Tree Cutting Act, 740 ILCS 185/0.01, which potentially triggers treble damages.

The defendants’ retained counsel did not either file an answer or appear for the case management conference. He was ordered by the Court to file an answer a month later, but failed to do so, so the plaintiff moved for a default judgment. The defense counsel was provided with a copy of the motion for entry of default, but counsel failed to respond or appear at the next hearing. In June 2011, the trial court granted default and entered judgment against the defendants.

A month later, the defendant’s counsel filed a motion to set aside the default, but failed to notice it for hearing. The plaintiff’s counsel noticed the motion for hearing and sent defense counsel notice. Counsel failed to appear for a scheduled case management conference, or for the motion hearing the following week. Accordingly, the trial court denied the motion to set aside the judgment, entering an order with findings. Ten months later, the plaintiff’s counsel filed a citation to discovery assets, and a week after that, the trial court entered an order removing the defendants’ counsel from the case and directing the defendants to retain replacement counsel. New counsel filed a second motion to set aside the judgment, attaching an affidavit from the client testifying that the client was unaware of the default or of former counsel’s negligence.

The trial court denied the second motion to set aside. The court held that defendants had established the existence of a meritorious defense and due diligence with respect to their replacement counsel, but had not demonstrated diligence prior to the entry of default.

The Appellate Court affirmed. A party was required to show three elements in order to be entitled to an order setting aside the judgment, the Court found: (1) a meritorious defense or claim; (2) due diligence in presenting it to the trial court; and (3) due diligence in filing the motion to set aside. The Appellate Court held that the defendant was not entitled to have the judgment set aside because it had not diligently followed the progress of the case and its former counsel’s efforts in the time between the initial complaint and the first default judgment and motion to set aside. Rather, the defendant “abandoned their own interest in the lawsuit and did not fulfill their duty to monitor the quality of [counsel’s] legal representation” during a nineteen month period.

Justice William E. Holdridge dissented. Although Justice Holdridge agreed with the majority that the defendant had failed to exercise due diligence in presenting its defenses to the trial court, he argued that the trial court erroneously believed it was without discretion to relax the requirement of due diligence in the interests of justice. Because Justice Holdridge believed that the defendants’ lost defenses appeared to have merit, he concluded that the trial court should have overlooked the defendants’ lack of diligence in pursuing the case and vacated the default.

We expect Warren County Soil & Water to be decided in six to eight months.

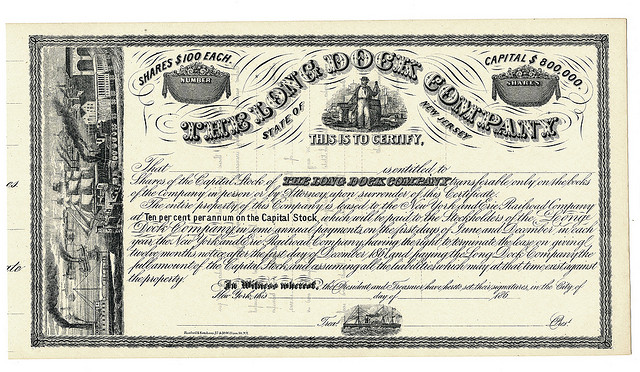

Image courtesy of Flickr by PlayingWithBrushes (no changes).